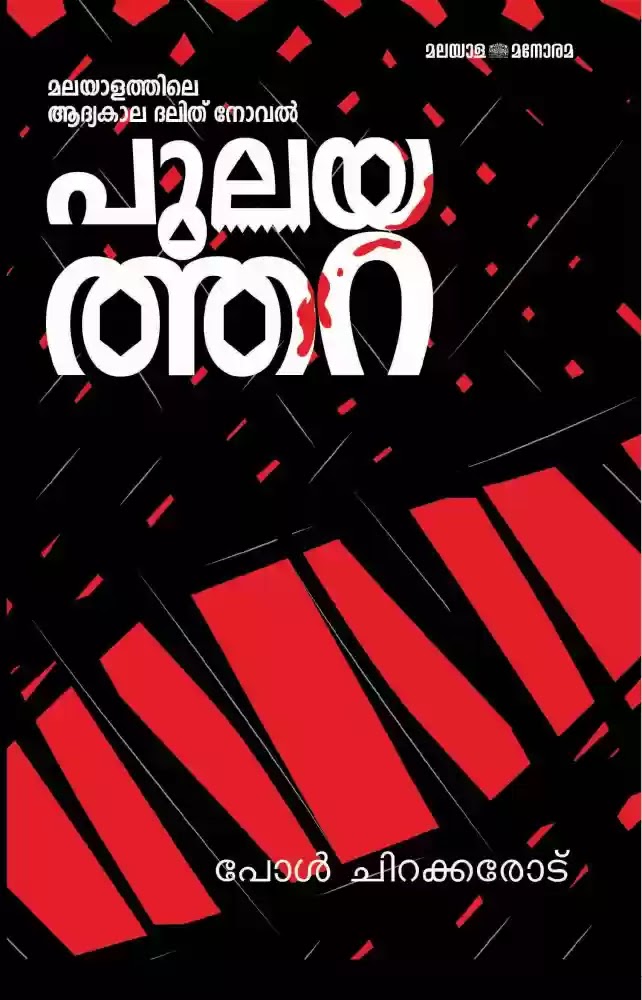

'Pulayathara' - Dalit life recovered?

(A contemporary reading of 'Pulayathara', which is described as the earliest Dalit novel in Malayalam literature. The article observes that the question of whether the optimism set forth by the novel's ending has yet been realized, lies in the text of the novel itself.

The textual extracts are independent translations from the Malayalam originals, intended solely for analytic purpose and may vary from the authoritative translations.)

'Soul? Does Pulayan have a soul? I will lock

you up if you don't work every day." – Koshi Kurian

-(by Mrs. Richard Collins - 'The Slayer Slain'- 1877.)

“But sometimes I fear that the poor people will not

have heaven. Sometimes it feels like we are undercast here as well as there.”- Paulos Pulayan

- (by Mrs. Richard

Collins - 'The Slayer Slain')

“They are Pathirivedas

(followers of priests). In other words, they are the followers of Jesus Christ.

They also have the same Veda (scripture) as the whites. They do not have

a specific caste. There is no caste. People of many castes have joined. When

combined, everything becomes one, like the sea.”

-

(Swaraswathi Vijayam (1892) – Potheri

Kunjambu)

In the honest, objective

perspective of an outsider, South African novelist Sheila Fugard, in her famous

novel 'A Revolutionary Woman', describes Indian caste system as the spring worm

in the bowels of Indian society through millennia. Fugard’s book, incidentally,

focuses on the subject of Gandhi's interactions in that country and the

Gandhi-Kasturba relationship. Literary expressions of Dalit living conditions,

described by one critic as a 'daily holocaust', *(1) have, however, acquired

authenticity only in recent times. Stories reflecting traits of Dalit

literature in varying degrees have come out in works such as Madam Collins' Ghataka

Vadham (‘The Slayer Slain’- 1877) or, even in earlier missionary

narratives. M.R.Renukumar observes that the post-eighties re-readings of the

works of Pandit Karuppan, T.K.C. Vaduthala, Paul Chirakarode, C. Ayyappan etc; were

inspired by the Dalit literature that emerged in Maharashtra in the wake of

Ambedkar's interventions from 1920 to 1956.*(2). Dalit literature in the formal sense grew in

Malayalam, only after it emerged first in Marathi and then in Hindi, Kannada,

Telugu, Bangla and Tamil. It is important in the history of Malayalam Dalit

literature that works problematizing

caste and religion (Ibid) were written in the sixties itself, although 'it

cannot claim any socio-political content that Marathi Dalit literature attained

in the light of Buddhism and Ambedkarism.’ 'Pulayathara' (1962) is

considered to be the next most important work in Malayalam Dalit novels, after

Potheri Kunjhambu's 'Saraswatheevijayam' published in 1892 and TKC

Vaduthala's 'Katayum Koithum' published in 1960. But the question of why

the book did not occupy a prominent place in literary history either when it

was first published or in the decades that followed can only be explained by

juxtaposing it with a pervasive maintstream, upper-caste sensibility. 'The

ability of the dominant/upper class .. to simultaneously perpetuate their

superiority and the subordination of the masses in tune with the times by

creating social, cultural and aesthetic binaries is extraordinary' (Ibid). This

is the clearest explanation why 'Pulayathara' or other similar works did

not get the same acceptance as a novel like 'Randidangazi'. Such novels

(Randidangazhi) were obviously circumscribed by the didactic character

of progressive literature and proletarian political convictions, and found

solution to class conflicts in the magnanimity of the upper class characters who

attained class consciousness.

Generic Characters:

"The history of a

person in an invisible community will be the history of a community,"

observes the narrator, who is a research scholar, in Pradeepan Pambiri's novel

'Eri'. This observation is the precise explanation why in the stories of those

down-trodden/ colonial/ racial / casteist/ racist/ apartheid/ subaltern/

marginalised people, generic experiences become more important beyond the

personal, and why characterisation relies more on types and representations

than on individuals.

Pulayathara

depicts the slave/slave-like Pulaya lives of Kuttanadan comminities in the

timeline of the last decades of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th

century, through a few characters who are more symbolic than individuals, like Thevan

Pulayan, his son Kandankoran, and the upper’caste land-owner Narayanan Nair. One

morning, the ‘Janmi’ (feudal land-lord)

evicts a drained-out-of health Thevan Pulayan from the fields that have grown

emerald from his sweat and salt of more than six decades, on a non-existent

charge. It becomes a loss of paradise for the Pulayan, not because he has any

ownership-claim over that land, but, for the emotional and organic connect he

has with it. There are still more observations in the novel that mark Pulayan

as a part of nature itself. Beyond

the political slogan of ‘farm-land for the farmer’, the natural harmony evident

in the next generation through Kandangoran/Thoma can also be seen as a

foreshadowing of later geopolitical convictions.

“Annakkidathi

understood. Her husband was a part of that vastness.... He is the son of the

fields. The field is his Karmabhumi (mission area).”

The Janmi sees a growing threat in Kandangoran, who

was possessed by the new generation's quest for independence. It is the time

when communism was taking root. Thevan and his son, who have lost their abode

and livelihood in one fine morning, knock at the hut of their old friend

Pallithara Paulus, who was 'Kilian Pulayan' earlier, looking for a place to

rest.

Paulus, who was allowed

to build a hut in the church-owned land as a converted Pulayan, has no

objection in accommodating the new guests. But Maria is worried about the

additional burden of finding means for more mouths and is not so happy. When she

expresses it overtly or covertly, it is too much of an affront to the dignified

Thevan and Kandankoran. The budding romance between Annakitathi and Kandankoran

leads him to opt for conversion to fulfil his love. This completes Thevan’s isolation,

who holds the old family/tradition, rituals and totems (Vetchupujas) as

sacred. The fact that the novel dismisses the old man to fade out into the

solitary path of mysterious/ mystical pursuits and to the margines of

narration, one might say, was a narratively an underutilized opportunity of

sorts. In the narrative style of the contemporary Malayalam novel, a unique

trend is gaining traction, to the point of getting tiring. Even if the story is

set in the timeline of colonial modernity, characters who are mostly dalit/

Adivasi and drawn from a bygone/ dying-out tribal culture and environments, are

paraded in an exhibitionistic manner, their minimal lives being exoticized as

an arena to exercise the author’s post-modernist narrative skills. In a sense,

the marginal lives exoticized in mainstream literature today are a Kerala

variant of Orientalist subservience perched in postcolonial narratives

in-reverse. This style of writing becomes a shortcut to public consensus as the

critical world either fails to, or opts not to, raise the question where these

expressions intersect with social life in any manner. The later life of Thevan

Pulayan would have provided ample opportunity for such a temptation. Be that as

it may, here the novelist condenses it all at once in the briefest of words.

'The old man Thevanpulayan is still

wandering on the edge of that fields. The old conch and the cowrie will never

go out of hand. It is a game of drawing a column on the soft soil and arranging

cones. And so will it continue. It is an unrecognized iteration of the hereditary

Velathan Pani (caste-ordained job).'

In Kandangoran, it is clear that the memory of his

father alive as pain and obligation. He decides that his and Annakidathi's baby

should be named after his father, and nothing, including his conversion, was too

big to stand in the way.

Social environment of conversions

The novel strongly raises

the historical question of what the new religion would bring to Pulayan. Those

who were branded as lower castes ventured into conversion as a means of

emancipation from the caste/slavery discriminations they had experienced and

not because of any particular spiritual vision.

"For the Parayan and

Pulayan who didn’t own a patch of land for their own, had a purpose in conversion. It is not the illusion of going

to heaven. If there is a heaven, it will be the upper caste Christians who will

take the lead there as well. You can’t imagine that they would abdicate

authority, just in the other world. How do you know that God will not be on

their side? Then Pulayan converts

to Christianity just to be buried in the Missionary

Cemetery. Only mission churches can provide him that facility. What else does

Pulayan, tired of working all day, dream of but the grave?"

But those Syriac

Christians who always proclaimed the glory of their ancestry were in fact

abusing the missionary gratuity:

“The mission land was

earned and handed over by the white missionaries who came from abroad. They

sought it to house the poor, newly converted Christians of this country. It was

the pious deed done by those good-hearted missionaries, seeing the

vulnerability of the new converts in the name of caste. The Syrian Christians

were clinging to them and climbing into the leadership position.”

But the centuries-old caste slavery was not so easy to

sweep away.

“In Uphill parish, Syrian

Christians were always Tambrakans (caste-masters/Lords) in the congregation.

Even though Parayan and Pulayan were baptised, they were still untouchables.

That status continues to this day.”

Even Poulus, who saw conversion as a true spiritual

experience, soon realizes this predicament. The term 'cat Christians' applies

to him as well. He too asks the same question those like Kali Parayan always

raised: “Were we converted just to be enslaved?” In fact, Paul was a symbol of

the reality of the caste system in the parish, where his position of church

committee membership was only to be displayed as a decoration, and he had no

part at all in any decision-making. The fact that all this was historically

true and that the situation like in the colonial Kerala of the 1930s-40s, the

time of the novel, did not change much in later times, shows why the book merits

discussion even today. But Kandankoran, who becomes Thoma and

marries Annakutty, does not have excessive expectations in conversion at any

point. This is an indicator of his sense of reality about the future. He does

not have any spiritual goal behind his conversion other than making Annakidathi

his own. He knows that what would remain for him, the master of toil, are those

fields that are wide enough to shed his sweat in. All he ever ached was for his

father: when tradition and his son’s love locked horns, he was unable to break

the ties of the former and went down the path of solitude. Kandankoran has only

one desire before that obligation: that his son be raised, with the same name

of that father. He has a firm answer to Annakidathi who is apprehensive if the

church people would accept the name Travanjoor Pulayan. "I don't care

if the parishioners would agree. I would call my son just that name.” But

he also insists that his son shouldn’t suffer what his father or he suffered: "I

will teach my son and make him somebody. I won’t let him go to work as a

coolie.”

When the fresh wind

blows

The novelist is very

optimistic about the beginning of the wind of a new era, starting with the

disputes between the old Christians and the new Christians in the church

committee and the church's stance against the growth of union politics. The

novel ends with Thomas and Annakutty deciding not to baptize their child or

give him a Christian name. However, the novelist also marks the fulness of

optimism not only through Kandangoran, who was a rebel from the very beginning,

but adds an epilogue-like sentence as the herald of a social transformation. "The

new generation has begun to speak." It can be said that beyond mere

inspiration, the politics of the expression 'speak' is also related to the

question of 'Can the subaltern speak?' For

a people whose language is obedience and silence, speaking itself is an active

negation of imposed/alleged subordination.

From the very beginning,

the novelist cherishes the idea that the gap between generations is the

harbinger of hopeful days.

"The matter of the

new Christians. They have no say in such matters. Or, if there is, it will not

be said. Who are they but hearers?',

'That simple man has no language.'

From here, at the very end of the first chapter, the

novel declares that the old generation accustomed to obedience and silence will

become obsolete:

'That

labourer of the next generation may defy the master.’

‘It will be the beginning

of a struggle.'

In a sense, it is the fulfilment of this declaration

that makes the end of the novel possible. Along with this optimism, the resonances

of the committed literature produced by the Renaissance and the progressive

period are also evident in the novel:

“Since community justice

today doesn’t approve. This system of denying rights to the labourer needs to

change.”

It is exactly the fear of a generation awakening to

the sense of entitlement that makes the sexton and the church oppose even the

sprouting of communist ideas and dub it as the biblical 'roaring satanic lion'.

“There is not even a

sense that rights are denied. How will complaints come up in the absence of

that feeling?'

It is also important that there are at least a few

characters in 'Pulayathara' who listen to the message of humanity put

forward by Renaissance, even as they are not directly affected. "No one

should call me 'Tamra' (Lord). The teacher who says, 'I don't like it' is one

of them. A brighter character is Pillechan, the tea-shop owner who speaks out

against discrimination in the church, despite great personal loss:

“You would convert poor

Parayas and Pulayas. Then you call them cat Chirstians. Mark that these are all

ungodly deeds.”

He also upholds the right of New Christians to convene

a meeting.

“Though it is true that

Pulayas have converted, they are still a separate community. Between them and

you, there is no connection at all. They have to have a meeting. What's wrong

with that?”

He also has answers to the accusation that the canon

of the Holy Church is being violated:

'Then why are you still

keeping them apart as new Christians?'

Since authentic Dalit

literature is literature written by authors from the same people, it can be

said that the novel has the soul of a novelist who knows the ins and outs of

Dalit life as "a descendant of Daivathan who was the first person to

undergo religious conversion in Trivancore". (Sitara I S). But the term

Dalit is completely alien to the text of the novel. The Maharashtra Dalit

Sahitya Sangh, organized in 1958, used the term precisely, but it came into use

again still later in the Malayali community. M.R. Renukumar notes that 'Dalit

literature in mainstream Malayalam became prominent with Bhashaposhini

publishing a 'Dalit literature edition''. Though there have been novels in

Malayalam featuring Dalit characters, especially Dalit Christian characters, from

‘The Slayer Slain’ onwards, they have all portrayed them as making

radical progress through conversion to Christianity. They were all descendants

of the Pulaya Christians who speak the standard Malayalam of 'Ghatakavadha'

and wax eloquent about the holiness of Christ's way. Writers like Potheri Kunjambu (Saraswathi Vijayam

-1892) shared the same bright and emancipative view of conversions, which,

incidentally, explains why the Dalits or other untouchables of colonial times

often viewed the British in higher esteem and were not that eager to

participate in anti-British struggles, at least in the early stages of the

nationalist movement. When asked why he didn’t want the low castes to prosper,

Kuberan Namboodiri (Saraswathi Vijayam) reacts that Bhrahmavu has it is

so ordained as purgation for the sins they committed in previous births and

that it was punishment for bhrahmananinda (irreverence to Bhrahmanas).

He adds that attempts to uplift them would amount to disrespecting god’s will.

He is worried the deluge and Khalki incarnation are imminent, since the whites

have jeopardized the labour-based caste-system by letting anyone do any job. Kunjambu

clearly thinks of conversions as a way to attain equality and a sense of self

respect for the Dalits and other lower-castes (heenajathi):

(Saraswatheevijayam,

Chapter.3). But

such idealizations were not realistic beyond the local variant of the colonial

hypocrisy of 'Whiteman's Burden' and 'Civilizing the Savages'. "Completely

in contrast to such novels, the writer here has brought out in book form what

actually happens." (Sitara I S). This observation about ‘Pulayathara’

is significant. However, the fact that none of the basic problems faced by

Dalits in the novel, like denial of social equality, lack of ownership of land,

religious discrimination and direct or indirect untouchability has been

resolved yet, colors the optimism presented by the novel's ending.

Speculations on the novel's ending

The ending of the novel is

imbued with certain very important questions and contradictions. In spite of

his heightened expectations for his son’s future, there is a sense of negation

of optimism latent in Kandangoran's characterisation. His determination to call

his son with the name of his father is a layered gesture in the context of his

attitude towards the church, the family and his tormenting paternal memories.

On the most obvious level, it signifies his blatant defiance of the

expectations of the church, which claims the likes of him as disciples of

faith, but wouldn’t share any privilege unto it, not even a semblance of

equality in Christ. The contemptuous treatment, and alienation they are made to

put up with, has in fact, resulted in a sort of double exile for them. They

were estranged to their parent communities, while the Christian community never

accepted them on equal footing. Thus, the converted Dalits were left in a limbo

of non-acceptance, suffering old wounds of untouchability in new forms. This experience

questioned the very motive of their initial conversion and showed them that ‘Pulaya’

fate was sealed with them, no matter they wore a rosary around their necks.

Upper-caste Hindu hegemony was simply replaced by aristocratic Christian

hegemony and nothing changed for the Pulayan. On a second level, his decision

is his quest to regain his identity. The socio-political impulses in the wake

of the emerging forces of communism, union spirit and class-conscious dignity

might have contributed to his new awareness that his is no shameful identity,

to be compromised for the illusion of a heavenly redemption.

Yet again, on a third

level, it is more personal and emotional. It signifies the manifestation of his

desire to reconnect with his father, a painful attempt to redeem the old man

and a symbolic way to relocate him. But here it is complicated, since it is

obvious that any such attempt is a doomed one. That it is unrealistic is proved

in his own experience. Pained as he is for the old man’s loneliness and

wretchedness, at no point does Thoma contemplate relocating him. Because he

knows theirs are incompatible ways of life. The way of the old man is all about

traditions, ritualistic, animistic worship of deities and totems. For Thoma,

nothing is more important than love. It follows that, even as he is willing to symbolically

relocate his father, he can’t afford to do the same in practical, pragmatic

sense. This is, in fact, the dilemma of the modern man, torn between tradition

and new ways of life. Nostalgia for the old, yearning for the new. That’s why

he doesn’t want for his son to follow the way of life supposedly

destined for the Pulayas, but wants him to carry a name as ancient as

generations. Sheer nostalgia, which has nothing to do with future. In other

words, by giving such a name to his son, who represents future, he would be

putting the youngster in the cross-roads of modernity versus tradition. Would

he pick as his father wants him to do, or as his father did do?

Given the fact that times are changing, the answer is obvious.

So the question is not whether

the parishioners would agree to christen the son of a new Christian with the name

Thiruvanjoor Pulayan. It is: will the son himself, who grows up educated and

removed from Pulayan's routine, tolerate the name, as Kandankoran alias Thoma

visualizes it? Convinced that outdated traditions are not more important

than love, Kandankoran did abandon his father and religion midway. What

guarantees that history will not repeat itself? How can we say that a son,

nurtured in modern education, wouldn’t find a name that marks the tradition of

two generations ago a burden? Although

the novelist does not directly suggest this, Thoma’s abandoning of his father

in all practical sense tells it all. It is quite unrealistic to expect a son,

who is not emotionally attached to that old way of life even as his father is,

to do what that father did not do. Who can vouch that he wouldn’t slip away

into the less-politically correct ‘hijra’ life of compromises the narrator in Sharankumar

Limbale's 'Hindu' lives, or to the fashionable aversion of the educated

tribal youth who turns his back on his stinking, ragtag Adivasi father in K.J.Baby's Nadugaddika

?

Sources:

1. Yogesh

Maitreya. ‘Pulayathara: A Dalit Man’s Quest for Home and Love’,

https://www.newsclick.in/pulayathara-dalit-man-quest-home-love, 28 Feb 2022.

Acccessed 21.07.2024

2. എം.ആര്.രേണുകുമാര്, ‘വീണ്ടെടുക്കപ്പെടുന്ന പുലയത്തറ’, മലയാള മനോരമ ‘പുലയത്തറ’ പതിപ്പിന്റെ ആമുഖം.

3. സിതാര ഐ. പി.,

‘പുലയത്തറയിലെ അടിയാള ജീവിതങ്ങൾ’, Ala/അല, A Kerala Studies Blog, Issue 69

4. ‘സരസ്വതീ വിജയം’, പോത്തേരി കുഞ്ഞമ്പു, അധ്യായം മൂന്ന്.