War-Time Alexandria: Resilience, Identity, and Sanity

(An

analysis of Ibrahim Abdel Meguid's No One Sleeps in Alexandria reveals

it as a passionate yet unflattering, realistic portrayal of a great city caught

in the wartime upheaval of World War II. The novel intertwines the lives of a

diverse array of characters from across Egypt and beyond, sharing both joys and

miseries, and contributing to the hybrid cultures that Alexandria is known for.

By blending history with personal narratives, the novel crafts a poignant epic

of humanity at the crossroads of violent shifts and cultural transformations.)

Fazal

Rahman

Founded by Alexander the

Great in 331 BC, Alexandria is one of the most historic cities in the

Mediterranean. Located on the northern coast of Egypt, it served as a center of

knowledge and culture in the ancient world. It was home to the famous Library of

Alexandria and the Lighthouse of Pharos, one of the Seven Wonders of the

Ancient World. Alongside Greek, Egyptian, and Roman influences, Alexandria

later became a significant meeting place for Islamic culture. It excelled in

science, philosophy, and art, and its strategic location established it as a

hub for trade and maritime exchanges, connecting Africa, Europe, and Asia. A

witness to the rise and fall of empires over the ages, the city remains a

cradle of rich heritage, including Greco-Roman ruins, Coptic churches, and

Islamic architecture. Merging historical grandeur with modernity, Alexandria is

celebrated today for its literary and intellectual legacy, vibrant cultural

scene, and its role as a bridge between past and present.

Alexandria also holds an

important place in world literature, often depicted as a city of mystery,

hedonism, and intellectual awakening. Its cosmopolitan character and rich

history have inspired countless literary works, both ancient and modern. In the

modern literary imagination, Alexandria was immortalized through Lawrence

Durrell's Alexandria Quartet. In these works, Durrell captures the

complexities Egypt and Alexandria faced between the two world wars. E.M.

Forster’s Alexandria: A History and a Guide offers a snapshot of the

city at the turn of the 20th century, blending history with personal

observations. André Aciman's Out of Egypt reflects on the city’s

cosmopolitanism and multicultural society, while the famous Greek poet

Constantine Cavafy, in his layered and evocative poems, explores Alexandria’s

timeless appeal as a meeting place of cultures. Additionally, the works of Arab

writers such as Naguib Mahfouz, Edward al-Qarat, and Youssef Zeidan delve into

its religious, philosophical, and cultural conflicts from non-Western

perspectives. Through these literary works, Alexandria emerges as a symbol of

cultural richness, fusion, and artistry that transcends borders.

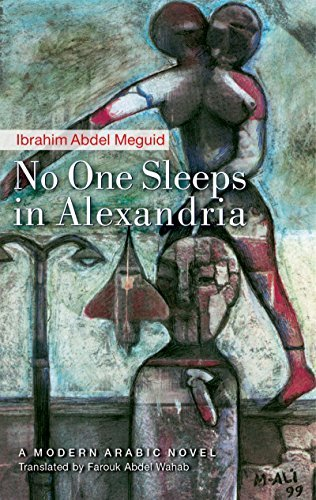

Egyptian novelist Ibrahim

Abdel Meguid further solidifies Alexandria's position in contemporary Arab

literature as a historical and cultural hub. His Alexandria Trilogy—comprising

No One Sleeps in Alexandria, Birds of Amber, and Clouds Over

Alexandria—is particularly notable. In an interview with Mogha Hassib for Arab

Lit Quarterly, Abdel Meguid described the inspiration behind the trilogy.

After completing No One Sleeps in Alexandria, he reflected on three key

historical phases that shaped the city. The first phase was marked by

cosmopolitanism and secular tolerance, even during the turmoil of World War II.

The second phase followed the Suez Canal crisis of 1956, when the departure of

expatriates drastically altered the city’s global character. This shift was

exacerbated by President Gamal Abdel Nasser's policies of nationalization and

socialism. Having been born in 1946 and raised in Alexandria, Abdel Meguid

witnessed the city’s transformation from a global society into a more insular

Egyptian city.

The second part of the

trilogy, Birds of Amber, captures this transitional stage, when memories

of the old metropolis remained vivid. The third phase, depicted in Clouds

Over Alexandria, reflects the impact of President Sadat’s alliance with

Wahhabi and Salafi fundamentalism in the 1970s, which, according to Abdel

Meguid, caused the city to lose both its global and Egyptian spirit, leaving it

exposed to a "desert culture." Abdel Meguid considers Alexandria

itself the protagonist of all three novels, which can each be read as

standalone works.

The Mosaic of Human

Relations

In No One Sleeps in

Alexandria, set against the socio-political ravages of World War II, human

relationships reflecting the complexities of love, faith, friendship, and loss

endure despite conflicts, forming the foundation of the narrative. These

relationships mirror the struggles and resilience of the city itself,

interweaving personal connections with broader social themes.

At the heart of the novel

is the profound friendship between Magd al-Din, a devout Muslim, and Dimyan, a

Christian. Their bond transcends boundaries, serving as a microcosm of

Alexandria’s diverse yet interconnected society. This relationship is not merely

evidence of secular tolerance but represents a deep human connection rooted in

shared experiences and mutual respect. A parallel to this is the warm bond

between Zahra, a village woman bewildered by the unfamiliar city, and the

elderly Sitt Mariam, the mother of Camila and Yvonne.

The novel’s backdrop is

the troubled state of war, as Magd and Zahra move to the hybrid vastness of

Alexandria, leaving behind the terrors of their farming village, plagued by a

long history of vendetta that haunted the family. The human connections that

withstand these conflicts sustain society in a web of interdependence. The city

itself, depicted as a living entity, becomes both a setting and a refuge.

Community relations during crises, such as airstrikes and resource scarcity,

reveal not only the solidarity that emerges in adversity but also Alexandria’s

role as a physical and emotional sanctuary.

The relationship between

Rushdie and Camila embodies youthful, idealized love that defies social and

religious constraints. Marked by moments of intense beauty as well as

challenges, their love symbolizes a romantic idealism. Camila’s ultimate

decision to join a convent reflects the weight of societal expectations.

However, her choice represents not despair but a search for peace beyond the

physical, while Rushdie finds solace through poetry and creativity. He would

pursue his passion for French language and literature, befitting the polyglot

city that was Alexandria.

Dimyan’s irresistible

attraction to Bikri, a mysterious Bedouin girl, inversely mirrors the

Rushdie-Camila dynamic of a Muslim boy and Christian girl. Dimyan struggles

with his uncontrollable passion for a girl not even his daughter’s age. He

consoles himself with a fatalistic belief that losing her is his predestined

pain. Bikri, who came from god-knows-where and vanishes in the same fashion, is

a symbol of mystery and otherness and represents the allure of the unknown.

This relationship further explores the novel’s central themes of love and

cultural boundaries.

Another deterministic

tragedy in the novel is Bahi’s life and his tumultuous relationships. According

to his doting mother, Bahiya, he was born with a halo, burdened from birth with

the fate of becoming an irresistible temptation to women, akin to the Biblical

Joseph. This predestined allure sowed the seeds of vendetta that embroiled the

male descendants of two dominant village families. Only three survived the

violence: one member from each family, who were hafids (those who knew

the Quran by rote), and Bahi himself, spared because he was not man enough for vengeance. Magd al-Din,

Bahi’s elder brother, describes him as a victim of his unchangeable fate,

comparing him to Job. “Some

people have been preordained to endure great pain. Job was one, and now Bahi.” Bahi’s tragic allure left women

devastated. The most enigmatic of these is Vageeda, an aristocrat who followed

him anonymously for over a decade, ultimately dying a vagabond at his grave in

Alexandria. Her story epitomizes the heartbreak surrounding Bahi, whose grave

is famously haunted by women, prompting the cemetery keeper to remark, “This

is the first deceased whose relatives are all women.”

Magd al-Din and Zahra are

compelled to leave their village and seek refuge with Bahi in Alexandria due to

the mayor’s machinations. Exploiting the terror about the re-eruption of the vendetta,

the mayor seizes their property. In contrast to the turbulent relationships

depicted throughout the novel, the bond between Magd and Zahra offers a story

of mutual trust and stability that transcends time and space. While Rushdie and

Camila’s passionate yet tumultuous love reflects the idealism and rebellion of

youth, Magd and Zahra’s relationship embodies traditional values of patience

and tolerance. Their resilience mirrors Alexandria’s endurance, and the city

awakens to serenity after the war’s horrors: "Alexandria became a city of

silver with veins of gold."

However, the novel does

not shy away from depicting the misogyny that mars human relationships,

particularly in its portrayal of rural life. From unprovoked brutal acts of atrocities and mutilation

carried out as part of tribal behavior of asserting male supremacy in the most

violent ways, these include ridiculous honor-killings based on flimsy rumors.

In one such case, a beautiful, innocent young wife is beaten to death, simply

because a neighbor, frustrated by her rejection, opted to spread stories of her

infidelity. Her husband didn’t even consider giving her an opportunity of

explanation. Even Alexandria, despite

its progressive facade, is not free from misogyny. The Mahmoudia Canal bears

grim testimony of pervasive violence against the vulnerable. We read that the

bodies floating in the Canal are always those of women and children.

Colonization and

Cultural Hybridity

The forces of

colonization and cultural hybridity play a decisive role in shaping the

dynamics of relationships in No One Sleeps in Alexandria. As a city

historically moulded by diverse influences, Alexandria became a true melting

pot during World War II. Soldiers, immigrants, and refugees from various

countries converged upon its streets, adding to its already rich and layered

cultural fabric. The lingering imprints of early French occupation and

subsequent British rule are deeply woven into the city's identity, influencing

the lives and interactions of its inhabitants.

Among the soldiers that

Magd al-Din and Dimyan encounter, there are men from across the world, many

hailing from colonized nations under harsh living conditions. These soldiers, mostly

uneducated, face an uncertain fate as they march toward a war with no promise

of return. Arguments, quarrels, and disputes are common, fuelled by racial,

caste, religious, and other prejudices. Yet, amidst these tensions, the novel

subtly highlights the possibility of cultural fusions, illustrating moments of

shared humanity that transcend divides.

For Indian readers,

several instances in the novel stand out for their resonance and historical

relevance. Each chapter begins with a lyrical quotation, often from renowned

authors, and Rabindranath Tagore’s verses are prominently featured. In a

striking moment, the penultimate chapter, where Dimyan’s death unfolds, opens

with a rare instance of death-wish lyrics in Tagore’s oeuvre, adding a poignant

layer to the narrative. The novel also captures the global reverence for the figure

of Mahatma Gandhi during this period. Through soldiers' discussions, allusions

to Gandhi’s ideals and India’s independence movement emerge as recurring

motifs. In one scene, when someone among the soldiers mentions the possibility

of India’s Partition, a rationale is raised as to why they can’t focus on

achieving independence first. Independence should definitely take precedence

over divisions. Tensions arise when Orientalist stereotypes provoke

confrontations between Indian soldiers and others, illustrating the simmering

cultural and racial prejudices within the imperial war machine. However, these

moments of friction are counterbalanced by profound admiration for Indian

leaders, particularly Gandhi. Safi al-Naeem, a Sudanese soldier, eloquently

extols Gandhi’s influence, declaring:

“India is a large country… It has

about three hundred million people. True, they have many religions, but they

also have Gandhi… He’s the one who’s fighting the English. He’s fighting them

without weapons. He tells the Indians to fast, and they all fast, to stop

dealing with the English, and they all stop, not to trade with them, and they

all refrain, to stand on one foot for a whole month, and they do. They are like

one strong man. Gandhi doesn’t have any army, but he has a whole people.”

This admiration, though exaggerated in its poetic

over-readings, underscores the interconnectedness of global anti-colonial

struggles. The presence of Indian soldiers and references to Indian politics

and the freedom movement lend a unique dimension to the novel's exploration of

cultural hybridity. These moments further establish Alexandria as a crossroads

of civilizations, where ideas and cultures mix dynamically while retaining

their distinct identities.

The novel delves deeply

into how Egypt, and particularly Alexandria, negotiated the complexities of

colonial rule. The war introduced new cultural confrontations, intensifying

tensions among the city’s inhabitants. Alexandria was the battleground for

rival colonial powers, especially Italy and Britain, each vying for supremacy

over the Mediterranean’s most vital port.

Against this turbulent

backdrop, the resilience and adaptability of Alexandria’s people emerge as

central themes. The novel celebrates their ability to endure and thrive amidst

external pressures and internal strife. This resilience is the enduring value

that the author upholds in this opening installment of the Alexandria

Trilogy.

Confluence of Modernist Narrative

Techniques and the Historical Novel

The structure, themes,

and stylistic choices of No One Sleeps in Alexandria blend modernist

literary practices with the enduring elements of the historical novel. This

fusion allows the narrative to intertwine personal stories with historical

traumas, offering a profound observation of wartime Alexandria. The aesthetics

of modernism—fragmented narrative, psychological depth, and a complex interplay

between individual and societal interactions—are evident throughout the novel.

Rather than adhering to

traditional linear storytelling, the polyphonic narrative creates a mosaic of

characters, reflecting the systemic disintegration and turmoil of wartime

Alexandria. By rejecting the singular authorial voice characteristic of classical

novels, the narrative embraces pluralism, denying the notion of a singular

truth and instead amplifying the voices of the marginalized. Despite being

anchored in a specific historical period, the interweaving of past and present

underscores the narrative significance of time and memory.

The novel explores the

disruption of lives by the pull of tradition, accelerated by the forces of

colonial modernity, as well as the political, economic, and cultural conflicts

exacerbated by colonial rule. It juxtaposes personal lives with the larger forces

of history, exemplifying the interplay between the personal and the historical.

The psychological approach the author adopts delves into the internal worlds of

characters experiencing emotional and spiritual turmoil, often conveyed through

internal monologues—a hallmark of modernist classics.

The existential conflicts

faced by the protagonists—Bahi’s fatal charm and Dimyan’s impossible desire—are

emblematic of the crises of modernity. These struggles generate despair and

futility, threatening the characters’ very existence. These existential

undercurrents align the novel with modernist literature, as does its portrayal

of alienation. Whether among the soldiers, immigrants, and refugees who flock

to wartime Alexandria or the city’s restless residents on the verge of

displacement, all grapple with the sense of alienation brought on by colonial

domination and subsequent identity crises.

Furthermore, the novel

critiques ‘Grand Narratives’ like colonialism, nationalism, and religion,

situating itself firmly within the modernist tradition. The poetic imagery

interwoven throughout the narrative transcends its romantic tone to reveal

hidden truths about larger narratives. For instance, when the author writes, “The

boats sailed or steamed into the canal on top of two hundred thousand life

stories, maybe more,” it alludes to the silenced tragedies of laborers who

perished during the construction of the Mahmoudiya Canal. History says that its

construction started at the beginning of 19th century on orders of Viceroy

Muhammad Ali and that is what awakened the city from centuries of indolence and

led it to prosperity. The novelist is reminding us that there is also a silent

history of countless helpless people buried in its making, and, for that

matter, any other urban culture. Thus, the novel pays tribute to the countless

lives sacrificed in its making, thereby emphasizing the untold costs of urban

culture.

Magd’s emotional denial

of Dimyan’s death, as he witnesses his friend consumed by fire during a

bombing, is heightened through evocative metaphors that elevate Dimyan’s

suffering to a Christ-like realm. Magd reflects, “Dimyan did not die; he was

not burned. God had lifted him up to heaven, and he had seen him, otherwise who

was ascending on the golden horse, moving away into space from the fire of the

dragon?” This moment, laden with religious and mythical imagery,

encapsulates the novel’s blending of personal grief with universal suffering.

Also, it lends utmost dignity to the otherwise meaningless death of a simple

ordinary war-victim who would never make it into ‘grand narratives’ per se.

The influence of religious traditions such as the

Bible and the Qur’an is evident in the novel’s metaphors and imagery. The

author’s language, often highly evocative and poignant, touches upon both the

legacies and misfortunes of Alexandria, offering a lyrical homage to the city.

The meticulous depiction

of Alexandria, capturing the daily lives of its poorest inhabitants alongside

its historical and global dimensions, speaks to the extensive research

underpinning the narrative. It vividly recounts events from Europe and the

Eastern Front during the war, as well as battles in the desert to prevent

Alexandria’s fall to Rommel. However, the novel does not merely chronicle major

historical events; it also sheds light on seemingly minor occurrences

overlooked by official histories, such as the struggles of migrant farmers and

laborers.

That said, some aspects

of the novel have been critiqued for potential anachronisms. For example, one

Amazon reader review notes that migrant farmers from northern Egypt during the

story’s period (1938–1942) might have referred to desert dwellers as ‘Arabs’

rather than ‘Bedouins.’ Such critiques, however, do little to detract from the

novel’s broader achievements. Ultimately, No One Sleeps in Alexandria

stands as a eulogy to Alexandria itself. Loving, emotional, and

quintessentially Egyptian, it serves as a biography of the city, immortalizing

its essence amidst the sweeping currents of history and modernity.

Sources:

- Mohga Hassib & Ibrahim Abdelmeguid. ‘Ibrahim Abdelmeguid: ‘The Hero Is the City’,

Arab Litt & ArabLitt Quarterly, January 31, 2014, https://arablit.org/2014/01/31/ibrahim-abdelmeguid-the-hero-is-the-city/

- Abdel-Messih,

M.-T. (2005). Alternatives to Modernism in Contemporary Egyptian Fiction:

Ibrahim Abdel-Maguid’s No One Sleeps in Alexandria. International

Fiction Review, 32(1). Retrieved from https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/IFR/article/view/7799

- Reader Review in Amazon page: Adel

Darwish, ‘Love, Death, Friendship and war that brings Alexandira's

character to life’, Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 18 February 2019

- Nourhan Ashraf Muhammad. ‘''Comparing Lawrence

Durrell's Portrayal of the City as a Character in Justine to Ibrahim Abdel

Meguid's in No One Sleeps in Alexandria'', 16.04.2018. Comparative Literature Course paper Dept of English Literature,

Cairo University

Read

the article in Malayalam:

https://alittlesomethings.blogspot.com/2025/03/no-one-sleeps-in-alexandria-by-ibrahim.html

No comments:

Post a Comment