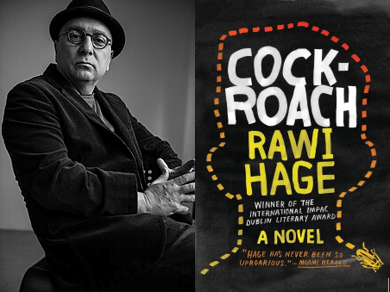

"Cockroach’: Portrait of the Illegal Immigrant as Insect

Rawi Hage, the Lebanese Canadian novelist, once remarked in

an interview with Quill & Quire: “I stay away from writers'

gatherings—I discovered there was nothing for me to learn at them. People talk

about the ins and outs of publishing; they don’t really talk about writing. I’d

rather hang out with my old taxi driver friends. They’re great storytellers.”

Sitting in a modest Montreal restaurant frequented by struggling writers,

expatriate proletarians, Hasidic Jews, and bohemian youth, Hage embodied the

spirit of an outsider—one who observes, rather than participates.

Hage’s journey to literary prominence was unexpected. After

working as a salesman, hotel waiter, and taxi driver, he transformed his

experiences into fiction, winning the prestigious International Dublin Literary

Award for his debut novel, De Niro’s Game (2006). His childhood in

war-torn Beirut, where power outages were frequent, fuelled his passion for

reading. “When there is no electricity, you can’t watch TV. So I read,” he

recalls, crediting literature with shaping his language and worldview.

Growing up amidst Lebanon’s sectarian conflict, Hage

witnessed the brutal arbitrariness of war, where identity alone determined

one’s fate. Fleeing the country in the early 1980s, he later studied

photography in Montreal, a discipline that influenced the dreamlike tension and

experimentalism of his writing.

A central metaphor in De Niro’s Game is Russian

roulette, an image famously associated with Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter

(1978). In one of cinema’s most harrowing sequences, three American soldiers

are forced to play the deadly game at gunpoint, reflecting war's dehumanizing

horrors. While Cimino's film faced criticism for its graphic violence, the

director defended its unflinching portrayal of brutality on grounds that in Vietnam

era, you cannot sanitize violence.

Hage’s novel echoes The Deer Hunter not only in its

protagonist George's nickname, “De Niro,” but also in its existential

explorations. Set against the backdrop of Beirut’s civil war and exile in

Paris, the novel portrays a generation for whom survival is precarious, and

life is recklessly discarded. Violence becomes the only means of resolution,

and identity oscillates between murder and suicide, reminiscent of Camus' The

Stranger.

If De Niro’s Game follows a young man escaping 1980s

Beirut only to face alienation in Paris, Cockroach extends this journey

into contemporary Montreal. The novel functions almost as a sequel, tracing the

descent of an unnamed anti-hero into the immigrant underworld.

At its core, Cockroach is a meditation on existential

crisis. Its unnamed narrator, an immigrant struggling with poverty, drug abuse,

and mental illness, undergoes therapy with Genevieve, a young and inexperienced

psychiatrist. From the outset, he proves to be an unreliable

narrator—obsessive, manipulative, and consumed by desire. A petty thief, he

breaks into homes to steal food and small possessions, his self-image merging

with that of the cockroach: unnoticed, unwanted, yet impossible to eradicate.

The novel is populated by equally displaced characters.

Reza, a Persian sitar player, is a compulsive liar who fabricates elaborate

stories to seduce women. Though the narrator harbors no real affection for him,

he tolerates his presence, occasionally sharing a joint or a night out. Even a

small debt—forty dollars—becomes a potential catalyst for retribution. Farhoud,

a gay professor and Iranian refugee, has endured imprisonment and torture. The

narrator, resentful of him, views him as a pretentious fraud masking his

poverty. In a petty act of disdain, he steals Farhoud’s love letters, not out

of necessity but simply because there is nothing else to take.

At the heart of the novel is Shohre, a strikingly beautiful

Iranian woman whose past is marked by unspeakable trauma. As a child, she was

repeatedly raped in an Islamist prison in Tehran. Her wounds remain raw,

shaping her inability to form deep relationships beyond fleeting encounters.

Her story mirrors the narrator's own pain: his sister, a victim of relentless

domestic violence, perished because he failed to avenge her. Encouraged by Abu

Roro, his mentor in crime, he once sought retribution but faltered at a crucial

moment, a hesitation that led to his sister's death. This failure lingers, fuelling

his quiet self-loathing and his earlier suicide attempt.

Through therapy, he is encouraged to find employment and

begins working at a Persian restaurant, where he meets Zeher, the owner's

daughter. Zeher embodies the evolving values of a younger immigrant

generation—one that embraces sexual freedom and rejects traditional

constraints. When the narrator accidentally witnesses her masturbating, he

perceives it as a rare glimpse into her inner world. Yet, unlike Shohre, Zeher

is not a victim; she is defined by agency, making choices of her own free will.

The novel's slow, meandering narrative tightens into a

sharp, cinematic climax when Shohre unexpectedly encounters her former

tormentor, now disguised under a new identity. Determined to reclaim her

agency, she enlists the narrator in her plan for revenge. For him, it is not

just an opportunity to help her; it is a chance to redeem himself, to atone for

his earlier inertia that cost his sister's life.

The novel's title evokes Kafka, but Cockroach is not

Kafkaesque in execution. As critic James Lasdun, writing for The Guardian,

notes, “Where Kafka writes Gregor Samsa's metamorphosis as a passion play of

Christ-like suffering and forbearance, Hage works the subject for something

much more caustic and defiant. Insecthood, for his victim, is a phantasmal

extension of his own multifaceted idea of himself: as immigrant outcast,

seething sensualist, Dostoevskian Underground Man, undetectable thief, future

inheritor of the earth, agent of exposure among the hypocritical bourgeoisie,

and all-round connoisseur of the tang and sting of reality.” Lasdun argues that

the influences of French novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline, playwright Jean

Genet, and American novelist William S. Burroughs are more evident in Hage than

Kafka.

A key motif in the novel is the biological superiority of

the cockroach—a creature that, unlike humans, can survive cosmic destruction.

This image reflects the existence of asylum seekers, forced to live in the

shadows, assimilating the knack of survival against all odds. The narrator,

describing himself and others like him as the "scum of the earth in the

capitalist enterprise," frequently employs black humor to navigate his

grim reality. His fragmented, surreal perspective allows him to

"undress" people, stripping them of disguises and pretenses.

Whether his sessions with Genevieve bring about real change

is irrelevant. His suicide attempt, mentioned early in the novel, is never

portrayed as genuine. Rather, his confessions serve as a narrative device,

weaving together disparate elements of the plot. His interactions with

Genevieve are not about seeking solace but about exposing himself and others.

Critics have observed that while Cockroach is stylistically

and structurally ambitious, its latter sections lose emotional momentum. Mary

Gaitskill, writing for The New York Times, argues that the novel's

juxtaposition of past misfortunes with a mission of revenge disrupts its

pacing. She also points to clichéd depictions of negative characters,

particularly those imitating French mannerisms, which dilute the novel’s sharp

critique.

Yet, despite these flaws, Cockroach cements Hage’s

reputation as a writer who masterfully blends style and substance. The novel’s

ending—shifting from poetic stillness to cinematic intensity—demonstrates

Hage’s ability to craft narratives that are at once intimate and expansive. The

narrator’s final act, killing a man of power, does not resolve his uncertain

life as an expatriate; rather, it plunges him into deeper complexities. But in

acting for Shohre, whose inability to avenge herself mirrors his own past

failure, he attains a measure of redemption—at least in human terms.

https://alittlesomethings.blogspot.com/2024/10/cockroach-by-rawi-hage.html

No comments:

Post a Comment